Few experiences are as remarkable as nature and wildlife encounters. Sometimes, rapid water cascades down a mountain slope leaves you feeling refreshed. Other times, the sound of chimpanzee hoots and grunts leaves your heart racing.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many such experiences were rendered impossible. Because of stringent health and travel restrictions, many tourism establishments were closed, and the reduced clientele in the sector resulted in staff layoffs and permanent business closures.

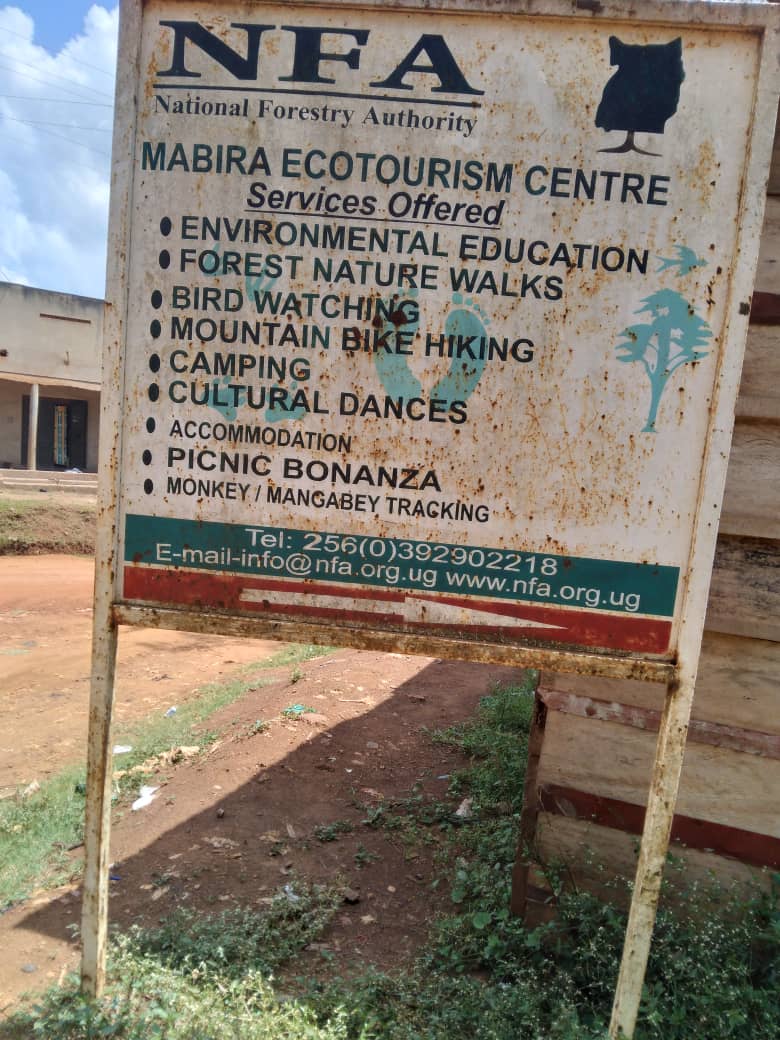

Sarah Atuhaire, a former guest administrator at the Mabira Ecotourism Centre, explained that the ordinarily bustling establishment quickly became a ghost town during the pandemic. All the hospitality work that she was often involved in was no more.

“I had to forget about the stability and prestige that came with working at the ecological site. I had to find a new way to survive, or my family would lack the means to survive,” Sarah explains.

According to UNCTAD, women make up most workers in the tourism industry, though they tend to be clustered in low-skilled jobs. Women’s employment, for example, fell globally by 4.2% in 2020 compared with 3% for men, as sectors in which women tend to work more – such as tourism – were ravaged by restrictions used to curb the spread of the virus.

It wasn’t just tourism establishments that were dealt a tremendous blow. Wildlife management and conservation work equally hit a snag. As revenue from nature-based tourism continued to dwindle, the risk of losing wildlife became more apparent.

Conservation managers like Johannes Refisch, programme manager for the United Nations Great Apes Survival Partnership Programme, quickly recognised the looming catastrophe.

In an interview on what the pandemic meant for ecotourism, Johannes explained that “the release of staff and suspension of law enforcement during the pandemic could easily lead to an increase in poaching and encroachment: first because there is little law enforcement; second, because community members have lost their income and have few other alternatives.”

True to this statement, countless headlines spelt out the grim ordeal that the pandemic had created in many wildlife sanctuaries. In Uganda, the death of Rafiki, Bwindi’s beloved Silverback, created a sadness that extended beyond the gorilla community.

“When I heard that Rafiki had been killed, I was devastated. It was like a member of my own family had died,” Florence Mbabazi, a guide employed by the Uganda Wildlife Authority, recounts the loss.

Wildlife managers and conservationists were called to think outside the box to facilitate wildlife protection during the pandemic. This call was finally heeded when individuals began to draw from their skill sets to present a temporary solution—virtual safaris.

In Uganda, the innovative tourism model was facilitated by six artsy youths and championed by Abiaz Rwamwiri, a tour and travel expert. The virtual safaris were broadcast under a campaign dubbed “Restart Uganda” to encourage visits to the nation after the pandemic.

“When tourism activities came to a halt, other countries, especially in Southern Africa, started using short videos to show how wildlife was thriving and couldn’t wait to host visitors again,” Rwamiri recalls the inspiration behind his campaign.

“I reached out to the Uganda Wildlife Authority and the Uganda Tourism Board and gave them this idea of having live trips to showcase tourism activities and what was at stake,” he remarks.

Virtual tourism, which dates back to the late 90s, has been an alternative to physically visiting some of the world’s most celebrated destinations. From experiences that require 3D glasses to those that feature 360° photos, virtual tours take on multiple designs based on one’s technical expertise and project objectives. The concept has also been applied in other fields such as gaming, real estate, education, and, the street view feature within Google Maps.

Conservation Efforts in Uganda

Over the years, Uganda has taken significant strides towards biodiversity protection, facilitated by wildlife custodians, local communities, and conservationists like Dr Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka.

Statutory instruments, including the Uganda Wildlife Act and the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP II), have also been designed to offer legal and operational support to the national conservation agenda. What is not clearly articulated in some of these instruments is how natural shocks, such as the one created by the pandemic, can be tackled.

Initiatives like the African Green Stimulus Programme(AGSP) have addressed such oversights. The African-led initiative was developed to “support the continent’s recovery in response to the devastating socio-economic and environmental impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.” AGSP has ambitious targets to support African governments and communities in attaining environmental sustainability and prosperity through financing, resource mobilisation, capacity building, research, technology, communication, and partnerships.

Conservation organisations such as the African Wildlife Foundation (AWF) have also stepped in to support nature conservation in Uganda. AWF boosted the virtual tourism model by hosting a series of virtual wildlife treks covering some of Uganda’s natural treasures, to deal with the tourism slump created during the pandemic.

Carter Smith, Craig Sholley, and Sudi Bamulesewa of the AWF expertly curated 3D and 2D video adventures of the extraordinary landscapes, wildlife assets, and local communities in Kidepo Valley National Park and Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in Uganda.

Smith believes that whereas virtual tourism could never fully replace physical safaris, it was a fantastic substitute for a period when people could not travel.

“It gave people a really good sense of what a real safari would be like,” she recounts.

“What is so nice about the virtual safari model is that you can involve any stakeholder you wish, to promote or to introduce, as long as the internet is accessible.”

The move to substitute physical safaris with virtual tours holds excellent tourism potential, especially in instances of limited contact and travel. It could also address biodiversity loss associated with economic shocks in the tourism sector.

For resource custodians like the Uganda Wildlife Authority, the benefits of this mode of tourism are somewhat automatic.

“If a virtual safari package includes gorilla tracking, instead of paying $700 to physically see gorillas, access to my virtual safari can be about $200. I will still pay the Uganda Wildlife Authority $75 for the gorilla permit,” Rwamwiri explains.

Nevertheless, for stakeholders like park communities, who often benefit only from physical activities such as trading in crafts or working in tourist establishments, more precise planning is needed to earn from the model.

These concerns on equity and benefit-sharing concur with resolution six of the fifth session of the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA 5). The resolution requested the Executive Director of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) to assist member states in taking measures to ‘foster cooperation in the context of pandemic preparedness, prevention and response and, more broadly, in the context of health-related research and development, including that involving genetic resources, while taking into account access and benefit-sharing frameworks.’

From his observation of the model in other countries, Rwamiri insists that virtual safaris can benefit local or vulnerable communities when virtual platforms are used for marketing local products like crafts online, or when some of the returns from virtual experiences are invested in community development initiatives.

However, it remains to be determined how exactly the virtual concept can be effectively designed to uphold the system, and equilibrium between humans, nature, and businesses in Uganda and how the engagement of all stakeholders, including women, youth, and vulnerable communities, can be improved.

What can be done for now is to find creative ways of complementing physical safaris with virtual experiences to harness the best of both worlds through strategic partnerships.

This article is part of the African Women in Media (AWiM)/UNEP Africa Environment Journalism Programme