By Solomon Tembang

With a baby strapped to her back, Josephine Ahanda* stands behind a table in a makeshift stand in the busy market of the Mokolo II Denier Poteau neighbourhood of Bertoua, a town in Cameroon’s East region. It is early in the morning of Friday June 4, 2021. The sun shines brightly though it is the rainy season, and the market’s hustle and bustle is at its peak. But Ahanda is frowning.

A few pieces of smoked antelope, monkey, deer and porcupine lie strewn across the table. Ahanda has been selling such products for five years, supporting her husband in feeding the family and sending their children to school. But since the arrival of COVID-19, the bushmeat business has been in steady decline.

“COVID-19 has impoverished us!” she exclaims. “There are no clients. There is also no meat coming from the hunters.”

Cameroon’s first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in March 2020. By August 2021, the number of cases exceeded 82,000 with over 1,300 deaths. This devastating disease, whose origin has been linked to wildlife trade in China, has had both positive and negative impacts on efforts to restrict the bushmeat trade in Cameroon. While many people are eating less bushmeat now, for a variety of reasons, others are eating more, as they run out of other options.

Supply and demand

Bushmeat trade — the commercial hunting and selling of wild animals for food — has been rampant in Cameroon in recent years. Vast numbers of monkeys, gorillas, snakes, antelopes, crocodiles, pangolins and other animals have been hunted, smoked and openly sold to be eaten. The trade has thrived, despite laws that prohibit the harvesting and sale of such species. That’s because Cameroonians of all walks of life have bought bushmeat from wildlife markets. COVID-19 has changed the dynamics.

In places like Bertoua, both supply and demand are down. Philbert Takam, a commercial motorbike rider there, says people used to hire him to transport bushmeat from nearby villages to the market. But since the outbreak of COVID-19, such trips have been rare. “This used to be a major revenue stream for me,” he says. “But now I rarely transport bushmeat.”

Several interrelated factors are at play. Customers are going to markets less due to COVID-19 travel restrictions and high transport costs. Job losses and rising costs of staple foods have reduced household budgets. Meanwhile, the price of bushmeat has nearly doubled, according to one trader in Bertoua. With fewer people buying bushmeat, fewer professional hunters are entering the forest. And both hunters and consumers may now be frightened of handling or eating wild meat, having heard that the virus emerged in a wildlife market in China.

Josephine Ahanda confirms that fear is a factor. She says that before the outbreak of COVID-19, the bushmeat market was vibrant, with many women selling huge quantities of game. It was the centre of bushmeat trade in the area, she says. Many traders came from as far as Cameroon’s capital Yaoundé, some 338 kilometres away, to buy bushmeat to sell to people who cook it in restaurants or consume it at home.

“But now, look at my table,” she says. “There is no bushmeat for me to sell. Even when we bring meat to the market, people don’t buy, saying that they are afraid of COVID-19.”

Illegal trade

At a wooden shack a few metres away, Joseph Ndzanga* is drinking a local alcoholic brew with a couple of friends. Ndzanga is a bushmeat hunter. Between sips, he explains how the pandemic has affected his livelihood.

“I used to go to the bush sometimes four days a week,” he says. “But since the outbreak of COVID-19, I go hunting once or twice a week. There are some weeks I don’t even go hunting. Many people are not willing to eat bushmeat because of the COVID-19 scare.”

He adds that wildlife officials have recently stepped up their crackdown on hunters, like him, who do not have permits.

Cameroon’s 1994 wildlife and forestry law forbids the sale and trafficking of endangered species, with penalties ranging from fines of between 3 million francs CFA and 10 million francs CFA, or imprisonment from one to three years, or both. The law respects the rights of indigenous people to hunt wildlife for home consumption, and allows other people to hunt non-endangered species if they have a permit.

This ‘permit de collect’, as it is called in French, costs 25,000 FCFA (US$45) for three months and limits the number of animals a hunter can kill. The permit allows hunters to use the meat however they wish, but getting hold of one is not easy because of cumbersome bureaucracy.

“For years now, we have not been able to have the permit because of the bottlenecks involved in obtaining it,” says Ndzanga. He, like many other hunters, continues to operate illegally.

‘Suppliers are no longer coming’

With illicit trade rife, in 2010, the Minister of Forestry and Wildlife issued an order banning the transport of bushmeat for commercial purposes. Nonetheless, tons of bushmeat continued to reach markets every week. But since the outbreak of COVID-19, this flow has dwindled to a trickle.

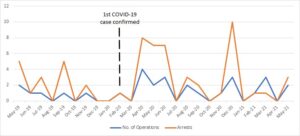

“Because of COVID-19, the world was almost at a standstill,” says Eric Kaba Tah, deputy director of wildlife law enforcement organisation, the Last Great Ape Organization (LAGA). “So, it became very difficult to move some of these wildlife products around. However, in a few cases, we could still see people using tricks to circumvent the bushmeat restrictions.”

The effects can be seen in Nyom, a bushmeat trading hub in Yaoundé I sub-division, in the Centre region. A bar called Chez Ma Po, located at Entrée Lycee Nyom, is a popular bushmeat-eating joint. In the afternoon of June 20, 2021, in a kitchen behind the bar, four women are busy roasting bushmeat on an open fire or slicing chunks of it to prepare the bushmeat pepper soup delicacy. People used to come from far to eat bushmeat there. But few do now.

“Meat is no longer available as before,” says the owner, Ma Po. She says she could previously source up to 50 pieces of bushmeat a week, but now the supply has dropped to far below 15. “Hunters scarcely bring the meat as they did before. Bushmeat has also become more expensive. We are now forced to deal with middlemen, unlike before when we got bushmeat directly from hunters.”

Poaching and anti-poaching

The species being hunted and sold are also different these days, according to Ponka Ebénézer Poincaré, a Bertoua-based specialist in conservation and management of natural resources.

“The species available in markets are mostly rodents, which can easily be hunted with traps in close-by farms without going far into the forest,” he says. “Species such as chimpanzees, monkeys, pangolins, deer and gorillas, which hunters need to go far into the forest to harvest, are scarcely found in the markets nowadays.”

To some extent then, the pandemic has been a blessing for Cameroon’s wildlife as it has reduced hunting pressure and disrupted the established trade in bushmeat. But there are also signs that some rural communities are now relying more on bushmeat as COVID-related restrictions have led to job losses, declining incomes and rising food costs.

Ponka says another negative impact of the pandemic is that some wildlife officials at checkpoints on bushmeat routes, fearing COVID-19, are unwilling to approach vehicles they suspect are trafficking animals destined to be consumed as bushmeat.

Anne Ntongho, senior monitoring and evaluation officer of WWF Cameroon also says anti-poaching activities slowed down after the arrival of COVID-19. She says that with fewer people to monitor what is happening — thanks to COVID-19 restrictions and fear of the disease — poaching may have increased in some communities.

Norbert Sonne, the African Wildlife Foundation’s country director for Cameroon, agrees. “When the pandemic initially broke out, people started avoiding bushmeat consumption because COVID-19 was linked to human proximity to wildlife,” he says. “Cases of bushmeat seizures reduced. However, this was short-lived. The rates of bushmeat poaching are rising.”

Food shortages

Sonne says that government-imposed restrictions aimed at containing the virus led to food shortages, and that the resulting food insecurity has increased pressure on wildlife. He mentions anecdotal evidence that people living near Campo Ma’an National Park and Dja Faunal Reserve are increasingly turning to bushmeat to feed their families.

A hunter, who gives his name as Pierre Didier, attests to this. He lives in Lomié, a town in the Upper Nyong division of the East region. The town is in the immediate periphery of the Dja Faunal Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Pierre Didier is sitting on a wooden bench at the back of his house. On the ground in front of him are about ten freshly killed animals. They include deer, porcupines, antelopes, monkeys, and pangolins.

“We eat some smoked and others fresh,” he says, smiling broadly as he points at a nearby grill fashioned out of a metal drum. On the grill, below which firewood glows with a light flame, is an animal that Pierre Didier is smoking.

“I now go to the forest for hunting more than before,” he says. “Because of the COVID-19 pandemic and its accompanying travel restrictions and preventive measures, there have been slight increases in prices of foodstuffs such as flour, sugar, rice and fish, among others, in our locality. So, my family and I now rely more on bushmeat for our subsistence.”

Alternative livelihoods

Sonne says communities around protected areas need to be self-sufficient in terms of food, or else they will turn to unsustainable exploitation of natural resources to put food on the table. To address this, his organisation is helping communities in Faro, Campo and Dja to adopt alternative sustainable livelihoods, such as beekeeping, agroforestry and adding value to non-timber forest products.

“The integration of cash crops such as cocoa and rubber with food crops with short growing cycles helps to meet household nutritional needs,” he says.

Some hunters are finding out on their own that other livelihoods are possible. In the evening of Saturday June 5, 2021, Pierre Awana* is leaning on the doorframe of his wooden and thatch house in Batouri, in Cameroon’s East region. He has been hunting bushmeat for decades. Some is consumed by his small household and the rest is sold to generate income. But since the outbreak of COVID-19, he rarely enters the forest to hunt.

“Previously, hunting was the mainstay of my family,” he says. “If I go to the bush in search of bushmeat [now], it is mainly for consumption within my household and not for commercialisation. The bushmeat business has dropped.”

“As a means to raise income for my family because I can no longer hunt and commercialise bushmeat, I have resorted to pig and poultry farming,” says Awana. “After doing this for just a couple of months, I have come to realise that it may be more lucrative than hunting and selling bushmeat. What’s more, it prevents me from often coming into trouble with wildlife enforcement officers.”

Uncertain future

While Awana has found an alternative way of making a living, the women in the bushmeat market of Bertoua’s Mokolo II Denier Poteau neighbourhood are in despair.

“You see how we are sitting idle?” says Helene Owono*, breaking from a group of women chatting. “There is no meat to sell.”

“Our livelihoods have greatly been affected,” she says. “We used to make money to save in [social groups] and plan for the future. But we cannot do that now. Our incomes have dropped drastically.”

Owono explains that she recently travelled to Belabo, a town 80 km away, to buy bushmeat but came away with only three pieces, whereas she used to buy as many as 50. “The money I spent for transport to go there was in vain,” she says.

Another woman interjects: “Now if you can have five or six pieces of bushmeat to sell, you just have to thank God. We can’t even pay our children’s school fees anymore. We are praying day and night for things to change.”

Mixed feelings

As Cameroon continues to deal with and recover from COVID-19, the fates of these women and of the country’s beleaguered forest wildlife will depend on various factors, from law enforcement to alternative livelihood development, from hunting rates to rural food security. A big factor will be the tastes and desires of consumers.

“Because COVID-19 was linked also to bushmeat consumption, I want to believe that many people are afraid to eat bushmeat, which is a benefit for wildlife conservation,” says Anne Ntongho of WWF-Cameroon.

But at a bar in the Nsimeyong neighbourhood of Yaoundé, on an afternoon in June 2021, feelings are mixed. Frederick Mvondo, who is drinking a beer at the bar, says he stopped eating bushmeat after COVID-19 was linked to a market in China. James Che, however, is one of a few customers who are eating bushmeat pepper soup.

“I don’t care whatever people say about COVID-19 having originated from animals,” says Che. “I still eat it as much as I did before. Bushmeat, to me, is tastier than beef, pork or chicken.”

*Names changed to protect sources from reprisals

(Pictures by Solomon Tembang, LAGA and WWF)