By Nalova Akua

For the past few months now, 52-year-old Aboukar Dalaye, Maroufa village-chief in northern Cameroon has had enormous difficulties feeding his cattle. For one thing, pasture land has become more and more scarce, and for another, he now treks through the town to lead his cattle to the river.

“As herders, we are bound to take our animals to the field every day to feed them with pasture and water,” Aboukar says.

“Now, it is difficult for me to feed my cattle, first, because of limited pasture space as a result of human-caused wildfires, and then, water scarcity,” he said.

“To get my cattle drink water from the Logone River, I am now obliged to lead them through the town which is a longer distance. If I use the normal, shorter passage as I have often done, it could cause another conflict.”

Aboukar belongs to the Choa-Arab tribe in the Far North Region of Cameroon. In December 2021, deadly clashes erupted between some members of the community and those of Mousgoum extraction over an issue Aboukar is now struggling to avoid: A cattle belonging to a Choa-Arab trespassed on the farmlands of Mousgoum villagers, leaving a trail of devastation in its wake.

In the confrontations that followed, at least 44 people were reported dead, another 111 injured while 112 villages were razed to the ground. The violence also drove more than 85,000 Cameroonians into neighbouring Chad, while 15,000 others were displaced internally according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

Earlier on in August, 32 people from both communities were killed, more than 74 others injured, while some 11,000 Cameroonians fled to neighbouring Chad during fighting which stemmed from yet another seemingly minor problem: the drowning of a cattle belonging to a Choa-Arab, in a Mousgoum water catchment pond. Nineteen villages were burnt down.

The Choa-Arabs are predominantly cattle-keepers in northern Cameroon, while the Mousgoums mostly rely on fishing and farming for subsistence. In order to respond to the climate crisis that has hit the region, the Mousgoums have resorted to creating water catchment ponds which enable them to farm and fish all year round. But these deep reservoirs so necessary to the Mousguoms, create death traps for cattle belonging to the Choa-Arab herders. The farmers and fishermen, in turn, allege that herders’ cattle have often destroyed their plantations and fishing areas.

“Herders trespass on fishponds which we struggle to build,” says 70-year-old Oumar Bara, a Mousgoum, and leader of Gawa Tata village in northern Cameroon.

“When we tell them not to trespass, they argue that they also need to eat; that they must graze their cattle in the surrounding pasture. These misunderstandings trigger conflicts,” he said.

Climate Variations

Choa-Arab and Mousgoum villages in northern Cameroon were created by the receding waters of the Lake Chad basin induced by climate change. The communities are just two of many others scrambling to survive on the rich, fertile land left behind by the depleting waters.

“The retreat of the waters has led to the creation of a hundred villages and emerging islands which are immediately occupied by populations of various origins,” Armel Sambo, a professor of history at the University of Maroua in Cameroon’s Far North Region said.

“These are mainly the Mousgoums, the Massas, the Djoukouns, the Choa-Arabs, etc. We also note the presence of other nationalities of West Africa, namely the Senegalese, the Malians and the Ghanaians,” he said.

Lake Chad is a freshwater inland drainage lake located in the Sahelian zone of west-central Africa at the conjunction of Cameroon, Chad, Nigeria, and Niger. The water level is controlled by the inflow from rivers notably the Chari from the south and seasonally, Komadugu-Yobe from the North West.

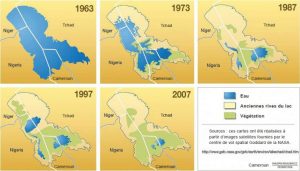

The surface area of the lake has witnessed dwindling fortunes in the past decades – shrinking from 25,000 km2 in the early 1960s to just 1,700 km2 following the severe droughts of the 1980s (almost 90%). But some studies estimate a peak of water extent in 2014 with its maximum of 14,000 km2 – although the estimates were usually based on partial observations. Other studies however put the 2014 level at 4,800 km2.

“Natural factors causing the gradual regression of the waters of Lake Chad include recurrent droughts caused by climate change,” Sambo said.

“Practically in all regions of Lake Chad, rainfall has dropped sharply since 1973. Added to this, is the silting up of Lake Chad, following the rise of very violent winds.”

“Anthropogenic factors include the difficulties of a concerted and rational exploitation of water, the multiplicity of dams (the Maga dam in Cameroon, the dam on the Komadugu River in Nigeria, etc.), the presence of dykes, poor knowledge of the texts (the Moundou protocol, the Lake Chad Basin Water Charter, the LCBC convention, etc.),” he said.

“We also have human factors such as the use of pesticides in agriculture, mining activities which strongly contribute to the degradation of the environment, water pollution, etc.”

Another researcher in the region said the geometric shrinking of the lake has created “an ecological disaster.”

“We have 60% decline in fish production, degraded pasture land resulting in a shortage of animal feed, livestock and biodiversity, internal exodus due to increased pressure on natural resources and conflicts between populations over the scarce water resources,” said Pascal Njah Sah, regional pedagogic inspector of geography in the Cameroon ministry of secondary Education in the region.

“The temperature of the region is increasing gradually over the years and even rising faster than (one and a half time) the global average,” he said.

“Lake Chad[used to be] blessed with aquatic and terrestrial biodiversity. Lake Chad basin comprises biosphere reserves, world heritage and Ramsar sites as well as wetlands of international conservation importance.”

“For years, the lake has been supporting drinking water, irrigation, fishing, livestock and economic activity for more than 30 million people in the region. It is vital for indigenous, pastoral and farming communities in one of the world’s poorest countries,” Njah said, further pointing out: “Climate change has fuelled massive environmental and humanitarian crisis.”

Conflicts linked to the scramble for increasingly limited natural resources (mostly arable land) due to climate change is common in Cameroon.

In the past, the Choa-Arabs have fought with their Kotoko neighbours, while in the Northwestern parts of the country, farmer-grazer conflicts are recurrent.

Growing Ethnic Rivalry

Aboukar may count himself lucky today for not losing any of his 10 children and three wives to the recent spate of violence, but he regrets “half of my cattle were looted by marauding Mousgoum men” as they fled to the relatively peaceful nearby town of Kousseri.

“More than half of the cattle in the village were looted,” he says.

“Nobody was killed in my village. But all the entire village was razed down. Now I live in a tent with my family. We are counting on the government to help us rebuild our houses.”

Oumar, too, didn’t lose any of his three wives or 12 children, but he lost seven cousins.

“Now I am penniless,” he says.

“The Choa-Arabs seized dozens of my cattle which they had in their keeping before the conflict. All my fishing implements were destroyed; so too were my millet yields. We fled to Chad.”

“In the past, misunderstandings used to prop up between us and Choa Arabs, but such misunderstandings were always resolved amicably in a family way. But this time around, the misunderstandings took a different proportion,” Oumar said.

Cohabitation is increasingly becoming difficult between the different communities found in the Lake Chad region. Sambo says the perennial conflicts in the region are the direct expression of growing pressures on dwindling resources.

“In the face of scarce natural resources (fertile land, fish, pastures), communities still tend to rely on identity and ethnicity to exclude one another,” he said.

“The Choa-Arabs, with their cattle, constantly in search of pasture and water, complain of the many water catchment ponds built by the Mousgoums. But the latter will not digest the complaints of those they consider newcomers and invaders.”

Targeted Killings

In a setting where dozens of tribes form a mélange, the security of everyone becomes worrying when violence breaks out. Alliance Abelegue Fidele, a humanitarian worker and researcher at Thinking Africa in the region recounts upsetting details which he witnessed.

“In villages here, people are grouped according to their ethnic group,” Abelegue says.“During the conflicts, when a group of Mousgoum fighters arrives in a Choa-Arab village, they would attack everyone there [with bladed weapons], assuming all of them to be Choa-Arabs and vice versa,” he said.

“That is why during the last conflict in December, for instance, villages which were not involved in the conflict such as the Peul (Foulbe) ethnic group, were spared of any harm.”

In villages jointly-inhabited by several ethnic groups including the Mousgoums and the Choa-Arabs, someone can be targeted simply because of their ethnic bodily feature.

“Mousgoums are generally identified here to be dark in complexion, tall and plump(fat), while the Choa-Arabs are also tall, but fair in complexion and not as fat as the Mousgoums. And so, during the conflict, once a Choa-Arab meets anyone exuding the description stated above, even if that person isn’t necessarily a Mousgoum, he will be attacked. The Mousgouns will act likewise,” Abelegue said.

The conflict has also put to test, the cross-cultural unions which bonded both communities.

“Sometimes, those who had intermarried are attacked by both sides,” said Abelegue.

Political Inclination

The hostility between Choa-Arabs and Mousgoums in northern Cameroon transcends just attempting to cope with climate change variations. It is also politically and economically driven. While the Mousgoums dominate demographically, their Choa-Arab neighbours domineer politically and economically.

“Of the 10 councils in the Logone and Chari Division, just one is headed by a Mousgoum – the rest are led by the Choa-Arabs,” said Oumar, the Mousgoum village-chief.

“Most chiefdoms are also headed by Choa-Arabs. To them, they have the license to do whatever pleases them because they dominate us economically and politically,” he said, further attributing the inter-communal rift to administrative recklessness and corruption.

“The Choa-Arabs bribe local authorities who regard us as the aggressor each time a conflict erupts. Each time we report the trespassing of cattle on our farms, local authorities tend to treat the matter lightly and don’t give it the seriousness it deserves. With such negligence, many Mousgoums simply decide to take the law into their hands and damn the consequences,” he said.

Sambo said the Choa-Arabs are seen to be favored in the distribution of elective positions such as mayors and parliamentarians.

“This is also a source of frustrations and antagonism,” he said.“In addition, the designation of traditional authorities in these localities often provoke conflicts between the different ethnic groups. Just recently, several more chiefdoms were created and this can only make the situation more and more difficult,” Sambo said.

Abelegue said besides dominating politically, the Choa-Arabs also constitute “the economic powerhouse” of the region.

“Almost all of the shops, stores, transport, cross-border trade, are controlled by the Choa-Arabs,” he said.

“That’s why when the conflict starts, they stop all commercial activities and go into hiding which makes life difficult for others.”

Aboukar, the Choa-Arab village chief, feels guilty that his tribe dominates politically, but deplores how it is now playing out in the recurrent conflict, describing it as “really unfortunate”.

“I don’t see why it (political domination) should create antagonism between cattle breeders and fishermen. It ought not to have concerned them,” he said.

“We have lived together peacefully for generations. And all of sudden, a useless conflict like this sparks up simply because of grazing land, or cattle? Brother against brother! It’s a pity to see innocent people lose their lives for a problem they know nothing about.”

Ticking Time Bomb

For now, precarious calm reigns in the region but mistrust and anger still simmer.

“The trust we had for each other has waned,” said Oumar, the Mousgoum village chief.

“We might greet each other when we meet but our hearts are still heavy. The grudge is still there. In the past, we used to intermingle with each other in markets and other public gatherings but now, we are careful to even venture into Choa-Arab villages,” he said.

Aboukar, the Choa-Arab village-chief, suggested the solution to the recurrent problem pitting his community and the Mousgoums lies in “guaranteeing safe passage for our animals into the river as well as guaranteeing pasture space”.

“Our Mousgoum brothers don’t want to see our cattle go anywhere near their farms, fishponds or villages,” he said.

Cameroon’s interior minister, Paul Atanga Nji visited the region during the last conflict in December, and told the belligerent communities: “Never again should this happen”.

“It is unacceptable to take the law into your own hands to loot, kill and perpetrate acts of vandalism,” he said.

“We are in a state of law and consequently, should respect the powers that be and the laws of the land. These are two communities living together in the same environment. Go to the local administrative authorities and lay down your complaints and it will be looked into,” he said.

“The traditional rulers and the religious authorities have to do their homework. Because if a traditional leader cannot even control his subjects, he is not fit to be a traditional ruler. Henceforth, their responsibility will be put on scale.”

But Abelegue frowns at the manner in which the conflict is usually handled, hinting that another conflict may just be looming on the horizon.

“Whenever a conflict breaks out between these communities, the soldiers are called in to stop the violence. As soon as a semblance of peace returns, local authorities and leaders of the two communities meet and discuss – and it’s over,” he said.

“The conflict has stopped for now but in reality, it is just on standby.”