Natives of Apouh in Ngog, a village located in the Edea 1st district, Sanaga-Maritime department, Littoral region of Cameroon, are still on a war footing with the Société camerounaise de palmeraies (Socapalm). The company has cleared almost 90% of the village to grow oil palm. Industrial farming deprives the local population of land needed for subsistence farming. “Socapalm has taken over all our land. Our houses are surrounded by oil palms. There’s nowhere left for us to grow the food we’re going to eat. On the few rare spaces we have left, the plantains and Cassava have been dried out by aerial pesticide spraying. We live in the village, but it’s in town that we go to buy food”, says Félicité Ngon Bissou, president of the Association of women living near Socapalm in Edea (AFRISE).

For the past ten years or so, industrial agriculture and rural farming have been at loggerheads in Apouh à Ngog. In April 2023, His Majesty Mercure Ditope Lindoume, the traditional ruler of this community of made of around 300 people, was taken to administrative custody on the instructions of Cyrille Yvan Abondo, Divisional Officer of the Sanaga Maritime department. The chief and his followers had fiercely opposed the replanting of palm trees behind their homes. “Our aim is not to block Socapalm’s activities. We think that after more than 60 years of expropriation of our land, the company should free up at least the area around our houses, that is around 250 hectares, so that we can produce enough to eat”, maintains the 2nd degree chief.

Spread over 58,063 hectares at its Edea site, Socapalm is 67.46% owned by Socfinaf, the Cameroonian subsidiary of the Socfin group (Société financière des Caoutchoucs), 22.36% is owned by the State of Cameroon, and the remaining capital has been listed on the Central African Stock Exchange (Bvmac) since 2009. In a reaction made available to us, the company denies any land grabbing, and says it operates sustainably and in the interests of the people living near its plantations. “We would like to point out that, as the legitimate owner of the land is the State of Cameroon, it alone has the power to decide on the updating of concession boundaries, and Socapalm cannot monopolise the land of neighbouring populations. In addition, contrary to allegations, there has been no rejection of any of the concessions. There are even fewer environmental hazards associated with aerial spraying. The company is audited several times a year by the certification body, by our consultant who has been working with us for several years, and of course by the authorities: the Ministry of the Environment, the Ministry of Industry and the Ministry of Agriculture”, Socapalm defends itself.

For the time being, the residents of Apouh in Ngog are not giving up. They have to travel 7 kilometres from their homes through huge palm plantations to practise subsistence farming on 150 hectares of land. For them, this is an insult compared to the 58,063 hectares of land occupied by the agro-industry.

In the South, a palm grove is eating up 60,000 hectares of forest

We are in the southern region, and more specifically in the Ocean department, just a short flight from Edea. Here, the deforestation relationship between industrial agriculture and subsistence farming is more than topical. And it is once again the oil palm that is at the centre of the quarrels. National investors plan to produce 180,000 tonnes of palm oil a year thanks to the “Camvert” project, a monoculture oil palm plantation planned for 60,000 hectares (three times the size of the city of Douala) in the districts of Campo and Niete.

At Camvert’s head office in Yaounde, the capital of Cameroon, Mamoudou Bobbo, the company’s Project Manager Officer, tells us that the project, launched in 2020, has already cleared nearly 2,000 hectares on the Campo site, for the planting of 250,000 palm oil seedlings.

The communities living in the vicinity of the project have had a difficult time due to it, despite the fact that they live mainly from fishing, hunting and gathering. “In the area destroyed by Camvert, we used to camp to hunt. We also went there to collect honey. Today, there’s nothing left”, says Henry Nlema, a member of the Campo pygmy community. For the few family farms that exist in Campo, daily life is no longer secured. The establishment of the palm plantation is causing wild animals, particularly elephants, to roam freely. “They wait until nightfall to come and eat the banana, Cassava and other plants that we grow behind our houses. We’re really discouraged”, says a woman in her fifties, sitting on a stool in her kitchen, which doubles up as her living room.

The conversion of forests to industrial oil palm cultivation is on a massive scale in the Ocean department, in the southern region of Cameroon. Since 2018, Bagyeli pygmies in the Bipindi district have been opposing a presidential decree granting 18,000 hectares of their forest to Biopalm, another agro-industrial oil palm company.

In the Centre region, 18,700 ha of sugar cane are grown as a single crop.

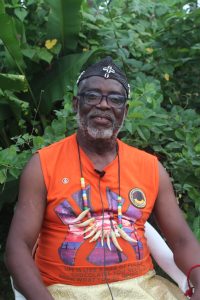

His Majesty Benoît Bessala Bessala, 2nd degree chief of Nkoteng (a municipality in the Centre region of Cameroon), has a bitter tone when he talks about the agro-industry that has been operating in his locality since 1964. “Nothing is going right. I can’t mince my words about that. The atmosphere is not serene between us, the indigenous populations, and the Société Sucrière du Cameroun (Sosucam). There are so many problems I can’t list them all here. If you’re coming from Yaounde, when you pass through Nanga-Eboko, you will have to block your nostrils, even though you’re in the car. Our river is totally polluted. We can no longer fetch fish and no measures have been taken. You know, Sosucam are tough guys. This means that wherever we go to complain, nothing will be done”, says the traditional authority indignantly, before casting his gaze towards the horizon in despair.

Located 136 km north-east of the city of Yaounde, the commune of Nkoteng’s main commercial activity is agriculture, which employs more than 90% of the working population. Mechanised farming is practised by Sosucam, an agro-industrial sugar company specialised in the growing and processing sugar cane. The sugar cane plantation covers an area of nearly 18,700 ha (on two sugar sites, MBandjock and NKoteng) and has an annual production of nearly 105,000 tonnes of sugar. The company, which is 74% owned by the French group Somdiaa and 26% by the State of Cameroon, employs 6,000 workers, mainly locals.

Despite the environmental impact denounced by local residents, the company is not the only one to have razed the local forest cover in order to set up operations, even though it has an environmental compliance certificate issued by the authorities. Through rural agriculture, practised with rudimentary technological means, the villagers are developing perennial crops. This is the case of Papa Lucas, a man in his sixties who owns 15 hectares of cocoa. “With this cocoa plantation, I’ve overtaken all those civil servants in Yaounde who do nothing in the office”, he says, walking towards his pick-up and swinging his bunch of keys. Like him, many other locals are clearing the forest to grow not only cocoa, but also coffee and oil palm, which is now being introduced in the district, with over 40 hectares already planted. According to figures from the delegation of the Ministry of Agriculture in the Upper Sanaga department, current cocoa production is between 25 and 30 tonnes, while coffee production is around 7 tonnes.

Benin

In Benin, village communities are at the forefront of the conversion of forests to agricultural use. Here, 54.8% of the population practises agriculture, particularly cotton, which is grown on 90% of farms and accounts for almost 40% of foreign currency earnings. Benin is the leading cotton producer in West Africa, producing over 730,000 tonnes each year.

On the question of whether subsistence farming or cash crop farming destroys more forest, the players are unanimous. Cash crops are responsible for deforestation in Benin. According to figures from the Beninese ministry responsible for the environment, nearly 100,000 hectares of forest are destroyed every year to expand cotton plantations, and to a lesser extent soybeans, rice, maize and palm oil. The communes of Banikora and Kandi, in the Northwest and North of Benin respectively, are the main cotton-producing areas.

Banikaora, is Benin’s leading cotton-growing commune.

Banikaora, is Benin’s leading cotton-growing commune. For the 2021-2022 season, this commune produced around 167,296 tonnes of cotton, or ¼ of national production, from an area of around 140,000 ha. That’s a lot of space, and for the 1st Deputy Mayor of Banikaora, Sabi Goré Bio Ali, it’s still not enough. “We’re limited in terms of space, because there’s the park and the Upper Alibori classified forest, which means we can’t expand our plantations,” explains the local councillor.

Banikora borders the Parc w and the Classified Forest of Upper Alibori But because of the protected status of these natural areas, and the government’s firm stance, cotton growers are extending their plantations beyond the borders of the protected areas. “In the past, a farmer used to cultivate two hectares at most. But now, with the use of herbicides, everyone is growing up to 10 ha or even 20 ha. This is leading us to destroy the forest”, admits Tamou Chabi, a cotton farmer in Banikaora.

Kandi

Kandi covers an area of 3,421 km2, with an estimated population of 177,683. Every year, the commune ranks second after Banikoara in terms of cotton production. At the end of the 2021-2022 season, the commune produced 68,000 tonnes of cotton from 71,000 hectares. Like Banikoara, it is part of the Alibori department, the agro-ecological zone of the cotton basin.

There are 20,000 cotton growers in Banikoara, divided into 194 village cotton growers’ cooperatives (CVPCs) Like Banikoara, Kandi also produces soybeans, rice and maize. According to the 1st Deputy Mayor of Kandi, we need to take a break from cotton production and come up with other alternatives for Benin’s development. “In the past, we were able to tell you that the rains would come on such and such a date. But today, because the plant cover is not there, the weather forecasts are contradicted by the reality on the ground. I think that where we are now, we have to stop and think of another spare part”, says Seidou Abdou Wahah, 1st Deputy Mayor of Kandi.

Civil society denounces industrial agriculture,

LE RURAL is an agricultural press group based in Benin. For some years now, it has been reporting on issues relating to agriculture, agribusiness, gender and development, research and innovation, health and nutrition and the environment. For its Director General, there is no doubt that cash crop farming is destroying the most forests in Benin. “Cash crops are essentially for commercial purposes. They are grown over large areas, unlike subsistence farming, which is intended to feed the family, and whose surpluses can be sold to cover other day-to-day expenses. It’s true that to date there are no up-to-date figures on the spatial occupancy of each crop, but I think that cotton tops the list of crops that destroy the forest the most. Because it’s one of the crops that requires a lot of land to be cleared”, explains Djibril Azonsi, Managing Director of LE RURAL.

In Cameroon, Aristide is one of the civil society players involved in the fight against deforestation. “I’d say quite bluntly that it’s industrial agriculture that’s destroying most of the forest. If you take, for example, the cocoa farming that some of our parents still practise in a rudimentary way, you will see that it does not totally destroy the forest, because cocoa is grown under shade. And even when forest communities practise agriculture, you will see that they still reserve forest areas for the collection of non-timber forest products or for traditional pharmacopoeia. Industrial agriculture, on the other hand, involves completely razing the forest, replacing it with non-natural vegetation, which in the case of Cameroon could be oil palm or rubber trees, the main crops grown by agro-industries. Or sugar cane”, explains Aristide Chacgom, coordinator of Green Development Advocates (GDA).

Public authorities advocate agroforestry

In Benin, where we were able to meet the Minister of Agriculture, there is a growing awareness of the damage caused to forests by both cash crops and subsistence crops. “It’s very common to see that the conversion of forests to farmland is gradually pushing us towards desertification, which will eventually starve us out. But you have to produce. I agree with you that family farming, practised on small areas, causes less damage to forests, it seems, but it does cause damage all the same. Because the way we farm, the way we clear land, the burning we do, the trees we incinerate so that our yams get the sun they need for proper tuberisation, is already deforestation. The problem is not just the scale used for certain industrial crops, but the method. For nearly 30 years we’ve had ample proof that if you have 40 well-distributed shea plants on a cotton field, you won’t affect the yield. So what can we do to get this logic into the heads of our farmers? That’s the whole debate,” says Gaston Dossouhoui, Benin’s Minister of Agriculture.

For the member of the government, the urgent task is to reduce the impact of agriculture on forests, without however trying to find out which type of agriculture destroys nature the most. To reconcile food production and forest preservation, in addition to agroforestry, the Beninese Ministry of Agriculture is advising farmers to use sowing techniques that do not require soil disturbance. Alternating certain crops on the same soil also helps to preserve its fertility. This is the case with yams and local crops such as Moukono and kajanus.

Fanta Mabo, Didier Madafime and Bernadette Nambu, with the support of the Rainforest Jurnalism Fund and the Pulitzer Center.